ARIADNE/WAYFINDING

What has Matt Written about War & Conflict?

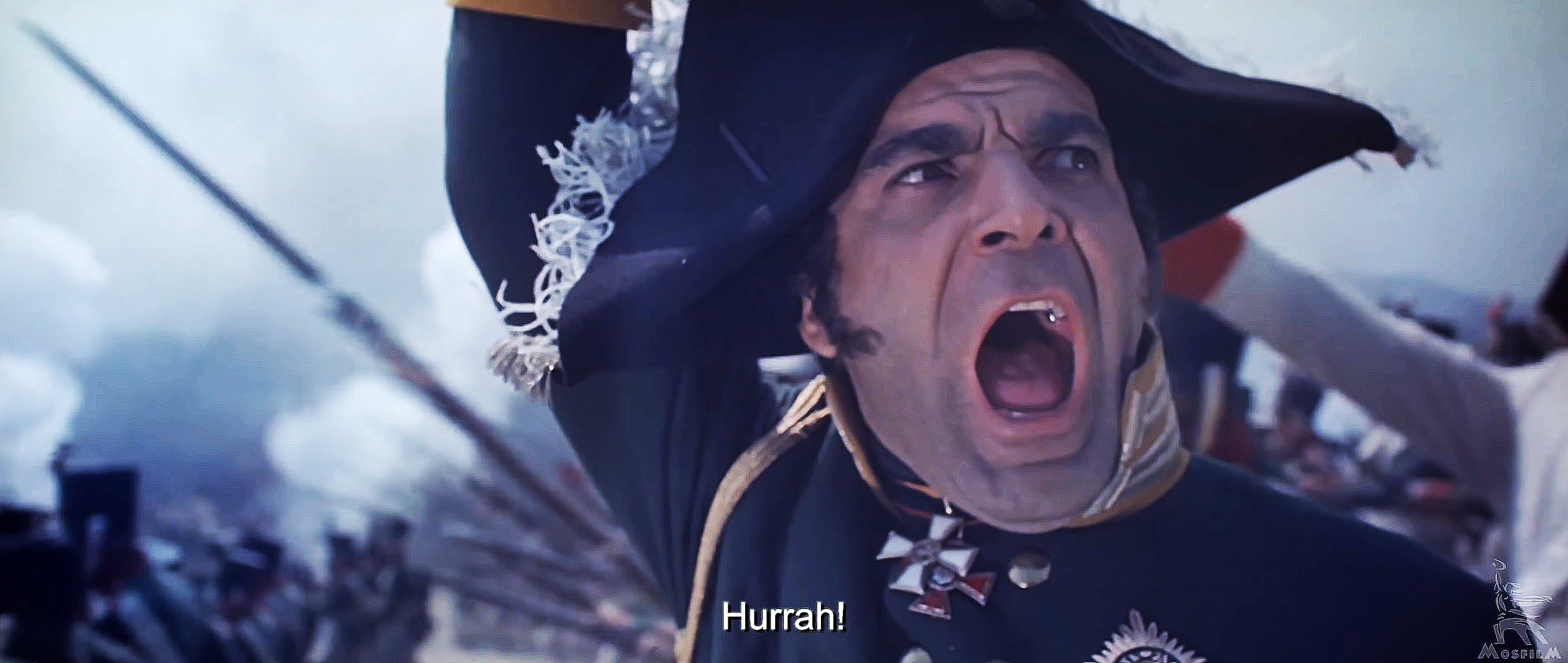

A sweeping tribute to Sergei Bondarchuk’s monumental War and Peace films (1966–67), celebrating their unmatched scale, artistry, and emotional intensity. A cinematic feat born of Soviet ambition and analogue grit, the series stands as a vanished pinnacle of historical filmmaking. Epic, intimate, and impossible to recreate. (Read)

Excerpt:

When older generations say that they don’t make movies like they used to, they’re talking about Sergei Bondarchuk’s War and Peace films, released between 1966 and 1967. An absolutely breathtaking series of four individual movies spread out over seven hours, recounting in elaborate, authentic and highly orchestrated detail, Tolstoy’s epic tale of Russian aristocratic and military perspective during the Napoleonic invasion of the early nineteenth century.

But epic doesn’t even come close to describing Bondarchuk’s films, which are enormous in scale, extraordinary in ambition, and astounding in depth. In short, they are a phenomenal example of precisely what the movies are all about, but also a sad archeological artifact of a craft lost to the digital frontier.

Critiques the film as a visually grand yet emotionally distant echo of epic cinema’s golden age. Drawing from Bondarchuk and Kubrick, it gestures toward greatness but falters in scale, casting, and conviction. A film about empire that, like its subject, feels too small for its ambitions. (Read)

Excerpt:

Epic movies made before the advent of digital technology are the best of movies. Casts of thousands streaming off into the distance of a lingering panoramic shot. Stories as big as their budgets. Tales of religion, of war, of love, all shot in incredible technicolor. Stories which showed us at our best, our worst, and often our most heroic. Epic movies are what the movies are made for. They are the purest of cinema. Truly transportational, they take us back in time to exotic places with strangely flawed characters, all arranged perfectly in a timeless widescreen bleeding from the edges.

Examines the legacy of the films Zulu and Zulu Dawn, contrasting their cinematic glorification of British colonialism with the brutal realities of the Anglo-Zulu War. It argues for contextual balance in storytelling, urging audiences to confront empire’s myths, not just celebrate its battlefield bravado. (Read)

Excerpt:

Even in an era of reparation, celebrations of Empire are still remarkably commonplace for the English, and there’s still a wealth of movies which still regularly air on British television which glorify its unsettling colonial past. The most common of these is Zulu (1964), which introduced Michael Caine to the world, and depicts the bravery of around a hundred British soldiers in the overwhelming face of three thousand eponymous Zulu warriors. Quotes from the film have passed into common language, and it’s routinely held up as a paragon of heroism from an age when the British held up heroism in the face of non-Britons as something to be revered.

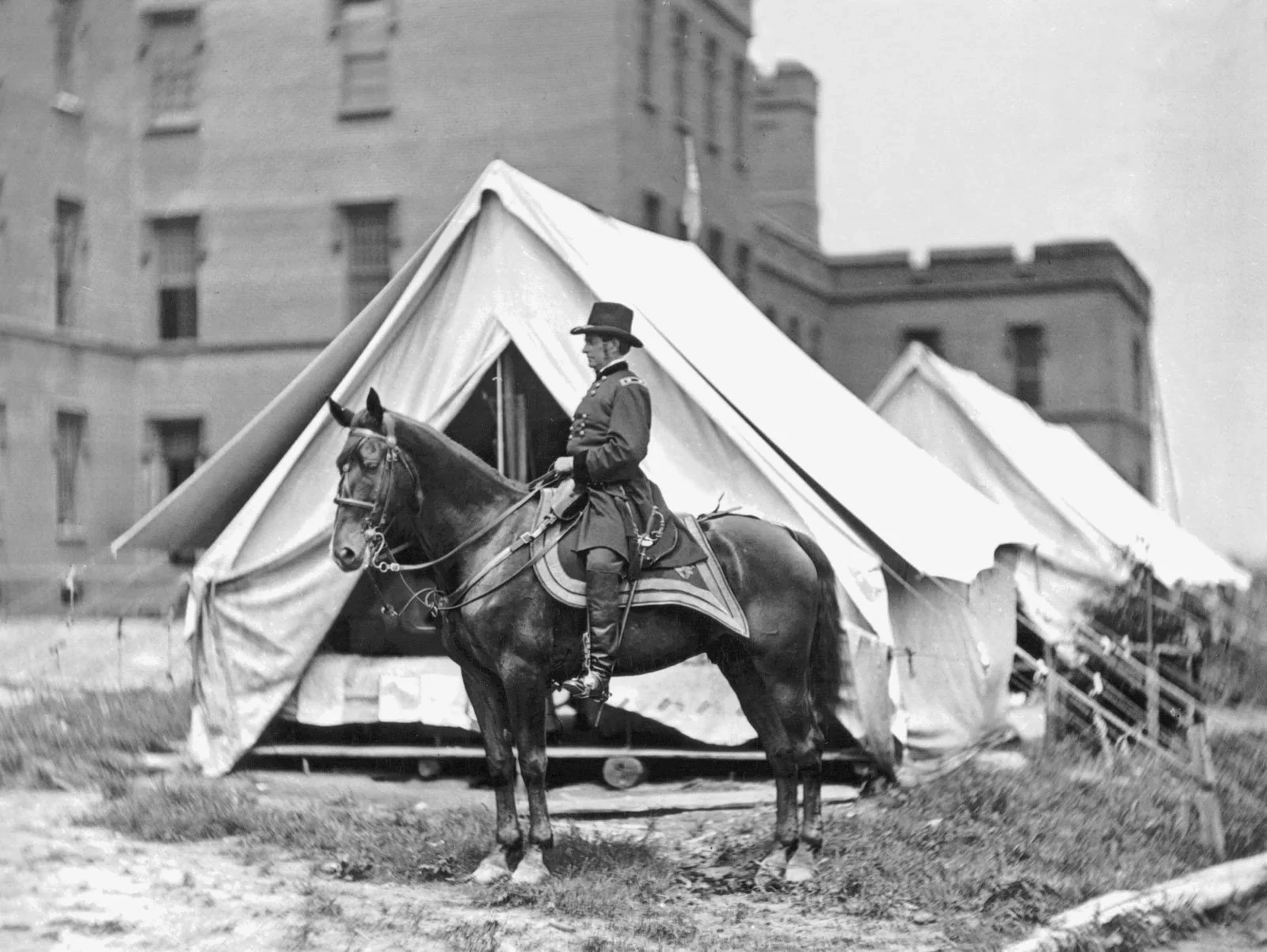

Explores Stanley Kubrick’s abandoned Napoleon project as a towering monument to cinematic ambition. Meticulously researched and never filmed, it remains a ghost of what could have redefined historical epic. Set against Bondarchuk’s grand but imperfect Waterloo, it reveals how vision, not just scale, defines greatness. (Read)

Excerpt:

I love Barry Lyndon, but feel Napoleon would have been even better. Increasingly separated from both the studio system and the concerns of the commercial outcomes of his work, Kubrick was entering a period of almost complete directorial autonomy, something he used to tremendous effect with the (only) four movies he’d create after 1971’s A Clockwork Orange. With near-limitless budgets, and broad latitude to create the stories he wanted to tell, such creative freedom also sadly feels like a relic of the past. We can create visually similar special effects to the ones captured in Waterloo, or aspired to in Napoleon, but we know they’re not real, and so we already miss something.

Reclaims Kubrick’s often-overlooked period epic as one of his most emotionally potent achievements. Anchored by a devastating final duel, it reveals cruelty, class, and cold precision beneath painterly beauty. Slow to build but unforgettable, it’s Kubrick at his most restrained, and his most ruthlessly exacting. (Read)

Excerpt:

Pacing is also important here. It’s a slow film, building with purpose towards a crescendo that’s absolutely worth it, but requires the investment of time, something we have less and less of in an era of push notifications, social feeds and intrusive advertising. With more and more of our attention spent on smaller and smaller consumption, devoting time to purposeful cinematic experiences becomes a luxury, but something few of us can afford.

Reflects on the British defeat as a cautionary tale of arrogance, poor leadership, and ignored warnings. More than military failure, it’s a human story of fear, misjudgment, and loss, urging us to see past statistics and into the lived experience of colonial catastrophe. (Read)

Excerpt:

The story of the battle of Isandlwana is one of hubris, poor decision making, poor preparation, and the misinterpretation of conflicting information. There are three main moments in the battle. Chelmsford’s decision to split his forces and head east. Pulleine’s lack of preparation in entrenching the camp. And the decision to spread the firing lines too far away from the supply of ammunition. All three result in humbling lessons for the British, and a sharp correction of the misplaced imperialist arrogance which came with the over-confidence in their technology and culture.

Explores how our drive for self-transcendence—our need to matter—can lead to both profound well-being and violent extremism. Through examining needs, narratives, and networks, it argues for constructive pathways like vocational, familial, and community programs that reframe significance into positive, pro-social meaning. (Read)

Excerpt:

The significance we seek in the pursuit of well-being and the good life can be both constructive and destructive. But through focusing on the needs, narratives, and networks we choose to align with, participate in, listen to, and surround ourselves with, we can reframe them to support more constructive, positive outcomes. We can actively augment and facilitate less conflict and suffering, reappraise the morally questionable, and most importantly, achieve the personal significance that’s so essential to our well-being.

Critiques how current appeals, like UNICEF’s, miss key opportunities to inspire giving. By shifting focus to individual narratives, shared resilience, and emotional proximity, the article argues we can enhance compassion through approach-based empathy, motivating not just awareness, but meaningful, sustained action. (Read)

Excerpt:

Buechner’s UNICEF article can greatly improve its capacity to motivate empathic prosocial and charitable behavior by reframing the dynamics of who we’re hearing from and adjusting the article’s order to focus earlier on positive shared experience. In addition, it should seek out opportunities for approach motivations of capitalization, affiliation, and desirability. In doing so, it may increase the intensity of our malleable empathic responses through spotlighting individuals, using tactics to draw them closer to us, and most importantly, focusing on the opportunities to empathize with the positive emotions of those impacted.

Frames Brexit as both rupture and regression—a self-inflicted severing from global integration fueled by nostalgic populism and weaponized imperial memory. Rather than reclaiming control, it has deepened isolation, bureaucratic burden, and cultural division, exposing the high cost of mythologizing the past as political strategy. (Read)

Excerpt:

Brexit is an example of how populist rhetoric of nostalgia, and a re-arguing of the globalist disagreements of the past in service of false opportunities for the future, has led to increasing global isolation, a distancing from the economic and cultural benefits of globalized convergence, and a backwards rebalancing of the laws and migration controls of empire (McKeown, 2007). Investment is suppressed, shortages are everywhere, and very little in the Brexit prospectus offered by the Leave campaign remains, except an even deeper convergence of xenophobia, national decline, and defiant unwillingness to reverse course. It’s an undoing of globalization through a weaponized use of the past.

Examines how Putin’s Russia weaponizes selective memory—especially of WWII—to shape civic identity, agitate nationalism, and justify war. Through state-managed nostalgia, historical revisionism, and media control, memory becomes political currency. What was once remembrance is now rhetoric, signaling not just the end of history—but the end of memory itself. (Read)

Excerpt:

Putin holds that ‘Neglecting the lessons of history inevitably leads to a harsh payback. We will firmly uphold the truth based on documented historical facts. We will continue to be honest and impartial about the events of World War II’ (Putin, 2020). Driven by grand collective narrative, the restorative nostalgia inherent in modern Russian politics, which ratchets up agitation to the point where it boils over from memory war into real war is a clear echo of Ernest Renan. That ‘unity is always achieved by brutality’ (Renan, 1882). And that ‘the essence of a nation is that all individuals have many things in common, and also that they have forgotten many things’ (Renan, 1882). The choice of what we are able to remember, what politicized nostalgia seeks to achieve, and what we choose to forget is increasingly malleable, manipulated, and militarized. But if the end of history is behind us, the end of memory is now upon us too.

Critiques the gap between online enthusiasm and real-world impact, especially in real estate. Exploring how movements like ‘Raise the Bar’ risk stalling in digital echo chambers, it argues that meaningful change demands more than likes, it requires empathy, offline action, and structures that convert awareness into consequence. (Read)

Excerpt:

Simply put, big change comes in small packages, especially online, and the rudimentary communication amongst individuals in real-time allows people to unite around a common goal as never before. In aligning around a cause, to the point where online activism becomes real-world change, is dependent upon empathy, the density of the networks engaging with those causes, and the strength of the content and conversations being produced inside them. Until such time as this moves beyond the slacktivism currently so prevalent within real estate groups online, and more into the realms of information, inspiration, and truly grasps the power to incite meaningful change, those conversations will never leave the groups that simply archive them.

Explores how too much expertise can mislead rather than guide, especially in real estate and digital marketing. Drawing from military history, behavioral psychology, and modern economics, it argues that overconfidence—fueled by abundant data—doesn’t improve decision-making, just belief in those decisions. When confidence outpaces accuracy, even experts can fail catastrophically. (Read)

Excerpt:

Overconfidence is sometimes described as happening when ‘people are blind to their own blindness’ While confidence is a critical aspect of restoring the housing market, more information does not lead to better decision making. People will continue to make the decisions they were going to make anyway, but increasing the flow of information will increase the confidence they have in those same decisions. But keep in mind that too much information, under the guise of unchecked transparency and disclosure, can often lead to miscalibration, wherein the consumer runs the risk of making the wrong decision.